Askhat Azhikhanov

PhD student, Institute of Economics and Business,

Kazakh State Technical University Satpayev K.I. (Almaty, Kazakhstan),

e-mail: Askhat@ababank.com

Tel: + 855 23225333 (office),

+ 855 98890777 (mobile), +855 23216333 (fax)

Abstract

The primary objective of this research is to investigate the earnings -

price relationship in the frame of the event study methodology. Using the

sample of 30 Small Cap and 30 Large Cap companies publicly traded on the London

Stock Exchange Main Market the study finds that Small Caps companies do react

stronger to Good and Bad news announcements, while Large Caps companies are

less responsive to these events.

Key words: stock, earnings

news, price, stock returns, small and large cap companies

Introduction

Earnings – price relationship is one of the most robust anomalies in

asset pricing literature. It is characterized as the continuance of abnormal

returns in the direction of earnings news after earning announcements. Early

studies try to interpret earnings – price relationship in the context of

efficient market theories (EMT) but fail to fully account for the observed

price drift. Recent research works have leaned toward behavior finance and

attribute the cause of earning – price anomalies to investors under – reaction

to earnings news (e.g. Bernard and Thomas (1989, 1990), Barberis, Shleifer, and

Vishny (1998), and Daniel, Hrsleifer and Subrahmanyam (1998))

The key implications for the accounting and finance research and policy

from the analysis of EMT were the following: first, financial statements are

not the only source of information for making investment decisions; second, and

more important, no trading advantages accrue to users of financial statements

because the information contained in them is instantaneously incorporated in

prices as soon as the information becomes public.

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) and Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)

contributed extra ideas, implying that since the expected return for a given

firm does not depend on risks that can be diversified away, information

regarding the outlook for a specific firm was largely irrelevant. The only

thing that mattered was the systematic risk of the firm and its relationship to

the total portfolio. Furthermore, CAPM and MPT influenced accounting theory

development by providing a model to measure the reaction of market returns and

earnings. Deviations from expected earnings could be shown to influence the

realised rate of return or, more specifically, the unexpected portion or

abnormal return.

All this led to the so-called market-based research studies that can be

classified into the following categories:

§ Tests of the EMT

versus classical approach

§ Tests of the

informational content of accounting alternatives

§ Tests of the

earnings/return relationships

The focus of my work is to test the earnings/return relationship in the

frame of the event study methodology. I will therefore proceed in the following

way: firstly, I will briefly review the landmark research papers that are

directly relevant to the questions I am attempting to answer. Secondly, I will

formulate my own hypothesis test and describe the methods and data set I intend

to use during my analysis. Thirdly, I will conduct the tests, describe the

obtained results and try to interpret deviations from the hypothesis. Finally,

I will summarise my findings and suggest if any further tests should be carried

out in the following area.

I. Theory and

empirical evidence

I will start my review of the research literature from the 1968 paper by

Ball and Brown that is thought to be the first comprehensive attempt to analyse

the earnings/price relationship. The two academics partitioned the firms in

their sample into good news/bad news groupings. Based on a firm’s reported

earnings, a company was classified as reporting good (bad) news if the reported

earnings were above (below) those predicted by a time-series forecasting

models. Based on this classification, two portfolios were constructed. The

findings were summarised in the comparison of the cumulative return of the

“good news” portfolio versus “bad news” portfolio. Good news firms enjoyed on

average abnormally positive returns, whereas bad news firms experienced

abnormally negative returns. By this research Ball and Brown demonstrated a

clear association between earnings and stock market reaction.

These results, as it often happens with empirical studies, have raised

more questions than were answered. Ball and Brown estimated that 80% to 85% of

the abnormal market performance occurred prior to the publication of the annual

report. This suggests that although earnings are meaningful measures of a firm’s

financial performance, by the time they are published they are outmoded and

have little or no market impact.

The market anticipated of reported earnings raised questions about the

timeliness of annual reports, and spurred a series of studies intended to examine

the “information content” of accounting data, which is measured by market

reaction to the announced earnings and its deviation from the expected

earnings.

To date, studies of the earnings/return relationship are among the most

widespread form of market-based research. Some research conducted in this area

was very broad in scope; some simply replicated the previous studies, with an

emphasis on methodological refinement. But all in all, there has not been

achieved rounded understanding of the role of accounting earnings in the

stock-return generating process.

The nature of the research can be classified based on the initial study

by Ball and Brown into:

§ Accounting variable

§ Market-based

variable

§ Tests of the

relationship between good news/bad news parameter and abnormal returns

Let us look in more detail into these three groups.

1)

Accounting variable

Ball and Brown used the sign of forecast error of annual net income and earnings

per share (EPS). Other researchers, like Beaver at al., considered the magnitude

of the error. Further, Foster examined quarterly earnings and found that

quarterly reports also possess information content.

However, a later research by Ball (1978) began to document

postannouncement drift, where positive (negative) abnormal return patterns

continued for some time after the announcement of good (bad) news quarterly

earnings.

2)

Market-based

variable or measurement period for market performance

Ball and Brown examined monthly returns over full year. Other studies,

depending on the issue analysed, used weekly (or daily) returns in the periods

immediately surrounding the announcement. The trade-off between using narrow

versus wide windows is that in the former case there is less risk that the

market could be reacting to information other than that being tested.

3)

Test of the

relationship between good news/bad news parameter and abnormal returns

Early studies, as I already mentioned above, grouped firms into good

news and bad news portfolios based on the sign or magnitude of the earnings

forecast error. Later studies explicitly related the response of stock returns

to earnings by the introduction of the earnings response coefficient (ERC).

The ERC is the coefficient b

in the regression equation R = a +

b∆E, where R and ∆E measure returns and earnings

change (growth) respectively. ERCs were typically found to be much lower than

expected.

ERC studies tested for differential reaction across firms and to various

components of earnings. Collins and Kothari (1989), for example, show that risk

and growth variables explain some of cross-sectional differences in ERCs.

Critical evaluation of

research findings

Despite the fact that many of the research papers tested relationships

that have not been tested before, many, like Lev, were critical to the prior research

results because they contribute to neither:

·

An understanding of how and to what extent earnings are used by

investors, nor

·

The debate of accounting policy makers

To a great extent, they attributed this failure to a fixation on the

part of researchers on sophisticated statistical techniques at the expense of

specification of fundamental relationships. This means that studies with

statistical significance often exhibited little or no economic significance.

For example, it was revealed that studies that examine the earnings/return

relationship tended to report low R2. On average, earnings could explain no

more than 5% of the variation in returns.

As a result of these criticisms, Lev, among others, suggested a more

enhanced approach to the research of return/earnings relationship that should

incorporate the following elements:

·

More careful analysis of valuation models as they relate to accounting

and earnings

·

Measuring earnings/return relationships on an individual basis rather

than portfolio basis

·

Averaging reported earnings over time and examining longer time horizons

·

Earnings components used in the research should incorporate all possible

adjustments in order to arrive at a more comprehensive and meaningful analysis.

When discussing the shortcomings of the research in the area of

earnings/return, I have to mention a number of discovered market anomalies that

question the validity of the EMH and some of the conclusions from the research

papers mentioned above. Below are a few of these market anomalies:

·

Monday effect. After the weekend, marker prices tend to open at lower

levels, suggesting an advantageous strategy of selling short at the Friday

close and covering the short position Monday morning. This anomaly is often

used by companies that make their earnings announcement after the Friday close.

·

Price-Earnings Ratio. Firms with low P/E ratios tend to outperform the

market even when returns are adjusted for risk.

·

Size effect. Smaller firms (measured by total assets or total

capitalisation) tend to outperform the market even when returns are adjusted

for risk.

·

The size effect is often attributed to the fact that fewer analysts

follow smaller firms than larger firms. Thus, not all information available

about these firms is immediately incorporated in stock prices, leaving room for

abnormal returns to be earned by those who trade on this information early

enough.

·

Post announcement drift. The EMH holds that stock prices adjust

instantly to new information. Empirical evidence, however, suggests that price

changes persist for some time after the initial announcement. In addition, some

researchers found the drift to be less pronounced for stocks having large

institutional holdings. However, little relationship was found between investor

sophistication and abnormal returns.

·

Over reactive markets: Contrarian Strategy. If the stocks were ranked by

their performance over a previous five-year period (the base period), those

firms with the worst base-period investment performance outperformed those

firms with the best base-period performance over the next three years. This

suggests that markets overreact.

This argument was further extended showing that when a firm’s earnings

decline, the market overreacts, driving the price down (and the book-to-market

value up) sharply. Similarly, when a firm reports good earnings, the market

chases the stock price up (and the book-to-market value down). Over time, the

extent of overreaction becomes clear and prices reverse, yielding

above-(below-) average returns for high (low) book-to-market firms.

I would like to conclude my brief review of research works in the area

of earnings/price by describing another study, by Ou (and later by Ou and

Penman), because their research contrasts Ball and Brown, discussed earlier.

Ou, similar to Ball and Brown, divided firms into good- and bad-news

categories, based on the previously reported earnings. The researcher then

added forecast earnings into the picture (derived from the regression using

eight variables, various accounting measures), which resulted in the formation

of four portfolios.

|

Portfolio |

Reported this year |

Predicted next year |

|

E+F+ |

Good news |

Good news |

|

E+F- |

Good news |

Bad news |

|

E-F+ |

Bad news |

Good news |

|

E-F- |

Bad news |

Bad news |

This research is different from many other studies mainly for two

reasons. First, the analysis is not motivated to show whether accounting

information is associated on an ex post basis with market prices, but rather

whether the information can be used ex ante as a basis for valuation. Second,

Ou broadens the set of accounting information by utilising the tools of

fundamental analysis (meaning that more attention was paid to changes in

accounting policies, ratio and warning signals analysis).

In the following research Ou and Penman tried to see whether a trading

strategy based on earnings forecast could prove to be fruitful. It was: the

average market-adjusted return was 14.5% per annum over a 24-month holding

period.

Finally, I would like to stress that approaches used by Ou and Penman as

well as by other researchers do not use fundamental analysis itself. In turn,

they rather utilise some of its tools. Fundamental analysis requires more

in-depth analysis, the nature of which varies from firm to firm. This important

attribute is missing from these studies, and this makes approaches used by many

academics significantly different from market practitioners like company

analysts.

II Sample, hypothesis and

methodology

In this section, I first discuss the data, hypotheses and then present

methodology I used to test these hypotheses.

Data

As the aim of this course work is not to conduct a comprehensive

research study, but rather to demonstrate understanding of the earnings/price

anomaly, the choice of the firms included in my sample as well as questions

raised are not new for the academic thought.

I work with the sample of 60 companies, a half of which are small-cap

firms and another half are large-cap firms. All companies are publicly traded

on the London Stock Exchange Main Market. The sample was created based on the

market capitalisation of firms: I opted for 30 top and 30 firms with

capitalisation below ₤100 million in the list, excluding the financial

companies.

The share price information and FTSE ALL SHARES Index return was

obtained using Bloomberg and Datastream databases. “Event”, which is the

announcement day of the annual earnings (results) of the firm, was sourced from

Bloomberg and London Stock Exchange. Both the actual and expected EPS were

provided by Bloomberg.

The events in the sample cover the period from 2005 to 2006. Narrowing

the sample to 1 year I intend to avoid discrepancies due to market sentiments –

the period from 2004 to 2006 period was characterised by predominantly bullish

mood with short periods of bearish behaviour.

Annual reports used for interpretation of the earnings/price

relationship were obtained from the companies’ websites or from the Bloomberg

database.

Hypothesis

I have formulated my hypotheses in the following way:

·

The share prices of the companies with earnings announcements above the

market expectations exhibit increase in the prices by percentage of earnings

surprise.

·

The share prices of the companies with earnings announcements below the

market expectations exhibit decrease in the prices by percentage of earnings

surprise.

·

Small-cap firms react stronger to positive (negative) announcements than

large-cap firms.

In expanding my analysis, I further examine the market

over-reaction and under-reaction to positive (negative) earnings news,

as well as, market reaction to non-earnings information.

Methodology

In this paper I use the standard event study methodology to assess the

market reaction to the earnings announcement.

The incorporation of earnings information tested within the 21-day

period, 10 days before the announcement and 10 days after the announcement. The

reason for that selection is the fact that there can be insider trading or

leakage in the market and the market can react prior the day of the earnings

announcement. I also use the longer event window in order to analyse the post-earnings

behaviour of the share price and examine the market over-reaction and

under-reaction to positive (negative) earnings new. At the same time, in order

to capture the price effects of announcement, I use following event window (-1,

0, +1), where 0 represents the earnings announcement day. I include day -1 and

+1 due to the fact that earnings announcement reported in various sources. As a

result the information may have been incorporated in share price not only on

day 0, but also on day -1 and +1depending on the sources (e.g. broker, news

media, etc.).

In order to calculate the abnormal return I use FTSE ALL SHARES index

return as a benchmark return. In this case I assume that the share prices move

in the same way and proportion as the index. Thus, the abnormal return was

calculated for each day and event as the daily log return of each company minus

the daily log return of FTSE ALL SHARES index for the same period.

![]() E(Ri) = Rmt ARit =

Rit - Rmt

E(Ri) = Rmt ARit =

Rit - Rmt

The price reaction on the earnings announcement was measured by the

three day cumulative abnormal return (CAR 3 DAYS) and calculated as the sum of

abnormal daily return of each company over the following event window (-1, 0,

+1). In order to examine the market over and under reaction I also calculate

the post announcement cumulative abnormal return (CAR POST) as the sum of

abnormal daily return for the post announcement 10 days, excluding abnormal

return of the first day (+1). This result will be compared with the CAR3 days

around the day of announcement. If:

1.

CAR3 days > CAR POST – then I observe over-reaction to the

announcement;

2.

CAR3 days < CAR POST – then I observe under-reaction to the

announcement.

In order to investigate the influence of the earnings announcement on

the share price I analyse the sign of unexpected earnings change, i.e.

deviation of the actual earnings from the expected earnings (earnings

surprise). I do not observe the deviation of the actual earnings from the

actual earnings the prior year, assuming that all the information about the

company is available during a year and most of the content of annual report

(about 85 to 90 percent, Ball and Brown 1968) already incorporated in share

price based on 3 interim reports. Thus, what really affects the share price on

the day of earnings announcement is unexpected earnings change or Earnings

Surprise. To calculate Earnings Surprise I use following formula:

Earning Surprise =![]()

In this case, if the actual returns are higher than the estimated ones,

then I can consider this news as positive news and the opposite, if the actual

are lower than estimated.

I further split the two broad samples of small and large cap companies

into three new sub categories based on the sign of earnings surprise: Good news,

No news, and Bad news. I categorize the news according to the deviation of the

actual earnings from estimated.

·

2.5% increase, considered Good News Event;

·

2.5%< Inc < -2.5%, considered No News Event;

·

< -2.5% decrease, considered Bad News Event.

In order to compare these sub categories, I further calculate average

cumulative abnormal return for each category, within two broad portfolios of

small and large cap companies.

Hypothesis testing

My hypothesis for all three portfolios, categorized by the type of event

is:

H0: the AAR on the first day after the announcement are insignificantly

different from 0.

H1: if the 0 is rejected the event has positively (Good News Portfolio),

negatively (Bad news Portfolio) or did not affect at all (No news Portfolio)

AAR across companies on the second day after the announcement of the Event.

To test the t-statistic, abnormal returns must be aggregated across all

firms and the standard error has to be calculated. The average abnormal return

across firms (AARt) for a sample of N firms at each time t within the event

window is given by:

Where AR it = Abnormal return for stock i at time t

N = Number of events in the sample

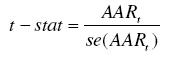

The t-statistic for the null hypotheses that aggregated abnormal returns

are equal to

zero is:

Where AAR t se = Standard error of AAR at time t

The standard error is calculated by dividing the standard deviation of

the abnormal returns into the square root of the number of events in the

sample. The t-test is a two tailed test at 5% significance level, with the

critical value taken from the t-statistic with n-1 degrees of freedom.

In my case, as the number of events in each portfolio is equal to 1,

t-stat will be calculated dividing the AARt by the SD.

In order to examine the magnitude of changes in share price (CAR 3 DAYS)

and changes in earnings (Earnings Surprise), as well as, correlation between

CAR 3 DAYS and Earnings Surprise, I build ordinary least squares regression

model using E-View program.

Finally, to analyse market reaction to non-earnings information and

taking into the account that Earnings Surprise may not adequately explain the share

price deviations, I include in my research a number of widely used factors that

may affect on the stock market reaction, such as:

·

Changes in dividend policy (dividend per share ratio);

·

Share buy back;

·

Target-Bid Announcement;

·

Changes in Sales growth;

·

Changes in Leverage;

·

Changes in Gross Profit Margin;

·

Changes in EBIT;

·

Changes in Liquidity;

·

Changes in Corporate Governance;

·

R&D.

III. Test results and their

interpretation

The earnings announcement sample illustrates the use of the abnormal and

the cumulative abnormal returns. The results of this research shows a plot of

the cumulative abnormal returns (CAR’s) over the entire 21 days of all three

company categories, Good News Event, No News Event and Bad News Event. ![]()

![]()

![]() The observations

support the hypothesis that earning announcements do indeed convey useful

information for the valuation of Small Cap firms. The result demonstrates that

the information contained in the good-news earnings announcement is useful in

that if good-news has been detected, the market follows in the same direction.

This is consistent with evidence found in the literature, Ball and Brown

(1969). Bad-news findings do match with my expectations as well. However, the

no-news findings follow a random walk, which also says that the market reacts

to no change-in-earnings information and there are other factors which also

influence the performance of the share price. For example, the Figure 2 shows even

higher volatility in the reaction of the No-news portfolio returns, and Large

Caps, being more transparent in their Corporate Governance submit dozens of

other qualitative news to the market such as M&A activity, corporate

restructuring etc.

The observations

support the hypothesis that earning announcements do indeed convey useful

information for the valuation of Small Cap firms. The result demonstrates that

the information contained in the good-news earnings announcement is useful in

that if good-news has been detected, the market follows in the same direction.

This is consistent with evidence found in the literature, Ball and Brown

(1969). Bad-news findings do match with my expectations as well. However, the

no-news findings follow a random walk, which also says that the market reacts

to no change-in-earnings information and there are other factors which also

influence the performance of the share price. For example, the Figure 2 shows even

higher volatility in the reaction of the No-news portfolio returns, and Large

Caps, being more transparent in their Corporate Governance submit dozens of

other qualitative news to the market such as M&A activity, corporate

restructuring etc.

At the same time, I have observed a high volatility of returns for my

Small Caps after the announcement day, which is consistent with most academic

studies and reflects their higher risk and lower liquidity.

Analyzing results of my test, I also observe that the evidence doesn’t

support completely the hypothesis that earning announcements convey information

for the valuation of Large Cap firms. The results demonstrate that the

information contained in the good-news earnings announcement is useful in that

if good-news has been detected, the market follows in the same direction with

small overreaction at the beginning. Bad-news findings do not match with my

expectations and no-news findings follow a random walk.

The test shows lower volatility of returns for Large Caps Good and Bad

news after the announcement day. This is consistent with most academic studies

and reflects lower risk and higher liquidity of the stocks.

Finally I find that Small Caps do react stronger to Good and Bad news

announcements, while Large Caps are less responsive to these events. This is

consistent result with my 3 hypothesis.

Small Caps T-test: The return is

reflected in the t-test with a significant t-observed of +2.39 at day one for

Good News Portfolio. The significance of the result means, rejecting the null

hypothesis that the given event has no impact on security prices. Thus, I

examine evidence that the market was surprised by the good-news of the

company’s earnings announcements and has adjusted to the bad and no-news, which

are both significant. Otherwise, the market expectations would have been

included in the stock prices prior the announcement.

If the investor would have put his money 1 day prior the event into the

good News portfolio, he would have achieved a 2.62% excess abnormal return over

the FTSE All Shares Index after the event.

Large Caps T-test: The return is

insignificant at day one for Good News Portfolio; though it follows the sign of

the event. The insignificance of the result means, accepting the null

hypothesis that the given event has no impact on security prices. The market

was not surprised by the good-news of the company’s earnings announcements and

has reacted positively to the Bad and No-news announcements, which are both

significant.

To check, if proxies mentioned in Part I of this paper can explain the

behaviour of my stock prices I have run a number of regressions:

·

Between CAR3 and Earnings Surprise and found R-squared of around 21% for

Large Caps and R-squared of around 25% for Small Caps. This confirms the results

of t-stat test and presence of other factors;

·

Unsatisfied by the explanatory power of this factor I include a number

of other factors and get a maximum R-squared of around 46% for Large Caps and

R-squared of around 40% for Small Caps which is still low.

Under and over reaction. Analysing this

part of the research I find a clear higher over reaction for Good news

portfolio of Small Caps, no excessive reaction for No news portfolio and less

under-reaction for Bad news portfolio. Investors seem to be over optimistic for

Good news and respond less to Bad news.

The results show under-reaction for Bad news and No news portfolios,

which adapt lately and irrelevant behaviour of Good news portfolio. For my

Small Caps portfolio Earning announcements are often one of the few sources of

information and investors respond to these news behaving irrational. At the

same time Large Caps produce more data and news as I have mentioned before and

market seems to be prepared and this information is already incorporated in the

share price.

Ball, in his 1992 paper “The earnings-price anomaly”, looked at various

reasons, provided by researchers to explain the persistence of the

earnings-price anomaly (e.g. the drift in the market response to earnings

announcements, implications of financial statements information for future

earnings and abnormal returns). He found that most of them do not adequately

explain the deviations. However, he accepted that the problems could come in

bundles, which are difficult to estimate.

Interpretations of earnings/price anomalies:

1)

CAPM beta risk. Beta estimation error could be correlated with earnings.

2)

Transactions costs.

3)

Liquidity and trading mechanism effects. Increase in abnormal returns

during the periods of illiquidity.

4)

Overstated t-statistics. Systematic understatement of standard errors of

various statistics by researchers.

5)

Earnings variables proxies for expected returns. Either CAPM or the

empirical market portfolio used in its implementation is misspecified, and the

independent variables proxy for errors in estimating expected returns.

6)

Substantial information production costs or market inefficiency?

Substantial costs of information acquisition and/or processing would be

encountered in implementing the trading rules simulated by researchers.

7)

The inefficient-markets hypothesis. The market-inefficiency explanation

requires prices to systematically provide unexploited pure-profit opportunities

from using accounting information.

I consider most of the factors stated above to be relevant for my portfolio,

which can explain deviations from the hypothesis.

Conclusion

The results revealed that my first hypothesis, positive earnings

surprise should be followed by increase in the share price, can not be rejected

for Small Caps portfolio which show positive and significant returns after the

day of announcement of annual results and should be rejected for the Large Caps

portfolio, which shows positive but insignificant CAR3.

Second hypothesis for the bad-news events can’t be rejected for Small

Caps portfolio, for which the annual results are sometimes one of the few

sources of information. Though, it can be interpreted differently for the Large

Caps, which show positive and significant result. Investors will have

incorporated the news provided in their security prices already. Over their

whole investment period they take different sources like interim reports and

other market data into consideration. The bullish stance has also prevailed

during the examined period among investors, who were overoptimistic.

Third hypothesis that Small-cap firms react stronger to positive

(negative) announcements than large-cap firms can’t be rejected as well and is

well-shown on the graphs. Risk and liquidity parameters have probably affected

higher volatility.

I examined the market over-reaction and under-reaction to positive

(negative) earnings news, as well as, market reaction to non-earnings

information and found that this seems to be the case for Small Caps portfolio

and partly inconsistent in the case of Large Caps portfolio.

Since I found different factors, which can explain stock price

behaviour, more work has to be done to better understand the strategic

decision-making of the investors and to explain factors, which drive the

performance of the share price.

1)

Ball and Brown, "An Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income

Numbers", Journal of Accounting Research, 1968, 6(2), pp. 159-78.

2)

Ball and Kothari, "Security Returns around Earnings Announcements”,

Accounting Review, 1991, 66(4), pp. 718-38.

3)

Ball, “The Earnings-Price Anomaly”, Journal of Accounting and Economics,

1992, 15(2-3), pp. 319-45.

4)

Ball, Kothari and Ross, "Economic Determinants of the Relation

between Earnings Changes and Stock Returns", Accounting Review, 1993,

68(3), pp. 622-38.

5)

Bodie, Kane and Marcus, Investments, 4th ed., Irwin McGraw Hill, 1999.

6)

Foster, Financial Statements Analysis, 2nd ed., Prentice Hall, 1986.

7)

Lasfer, “Research Project Management”, 2006, lecture notes.

8)

Lasfer, “Security Analysis”, 2006, lecture notes.

9)

Lev, “On the usefulness of Earnings and Earnings Research: Lessons and

Directions from Two Decades of Empirical Research”, Journal of Accounting

Research, 1989, pp.153-192.

10) Ou and Penman,

“Financial Statements Analysis and the Prediction of Stock Returns”, Journal of

Accounting and Economics, 1989, pp. 295-329.

11) Ou, “The

Information Content of Nonearnings Accounting Numbers as Earnings Predictors”,

Journal of Accounting Research, 1990, pp. 144-162.

12) QI Sun, “Stock

Price Reaction to Earnings Announcement Drift”, Working paper, School of

Business Administration, University of Wisconsin-Miwaukee, 2005

13) Winkelmann, “The

Impact of Earning Announcements on Security Returns: An Analysis of German

Mid-Cap Companies listed in the MDAX”, Dissertation, Cass Business School,

2002/

14) Bloomberg database

15) Datastream database

16) Thompson Financial

17) London Stock

Exchange: www.londonstockexchange.com

18) Companies’ websites